BuzzFeed News; Saul Loeb / AFP via Getty Images

Join HuffPost and BuzzFeed News for a Twitter Spaces conversation about how the Capitol riot is still altering US politics on Jan. 4 at 1 p.m. ET. Sign up to be notified when the Space begins here.

WASHINGTON — What is the punishment for someone who admits they joined in on an attack on democracy?

For Jordan Stotts of Minnesota, it was two years on probation, with two months of tighter limits on when he can leave home. He scaled a wall to join the breach of the US Capitol, was captured on camera shouting at officers in the rotunda, and vowed to return, posting on Facebook: “Patriots! I got kicked out but I’ll be back!”

For Lori and Thomas Vinson of Kentucky, it was five years on probation plus a $5,000 fine. Prosecutors had wanted jail time for Lori — she told an interviewer after she was fired from her job for participating in the riot, “I would do it again tomorrow” — but a judge didn’t agree.

For Boyd Camper of Minnesota, it was two months in jail. As he joined the mob streaming into the building, he filmed his trek on a GoPro. He told a news crew outside later, “We’re going to take this damn place.”

The task of fashioning justice for people who admitted to participating in the Jan. 6 insurrection has fallen to 22 judges on the US District Court for the District of Columbia. The court’s members — a mix of Democrat and Republican appointees — have made clear they believe the assault on the Capitol was serious and violent, and that people convicted of crimes deserve punishment. They just don’t agree on what it should be.

Some judges have bristled that prosecutors struck plea deals for low-level misdemeanors that limit the sentences they can impose. Some have imposed sentences that were harsher than the government’s recommendation; others have been more lenient. Some have questioned the varying sentences proposed by prosecutors across a spectrum of Capitol rioters who pleaded guilty to the same offense.

It is “no wonder,” US District Chief Judge Beryl Howell said at an October sentencing, that some people “are confused about whether what happened on Jan. 6 was a petty offense of trespassing or shocking criminal conduct that represented a grave threat to our democratic norms.”

Judges have had no patience for Donald Trump supporters trying to use the courthouse as a forum to relitigate President Joe Biden’s win in 2020. But the lack of consensus on the bench about what exactly justice should look like for each person who joined the mob mirrors a lack of consensus nationwide about how to think about the insurrection and its aftermath.

The most common sentence has been probation, with a short period of home confinement or a fine mixed in, according to BuzzFeed News’ tracking of every prosecution filed in the year since the Jan. 6 attack. Probation means people can mostly return to their normal lives, with conditions — they have to regularly report to a probation officer, get permission to travel, submit to a home inspection at any time, and hold a job. They can’t have guns or other weapons. Violating probation by committing new crimes or failing to comply with other terms is a standalone crime that can be prosecuted.

Nearly all of the 71 defendants sentenced as of the end of December pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor, with most deals featuring the same charge: illegally parading in the Capitol, which carries a maximum sentence of six months in jail and a $5,000 fine.

In more than half of these misdemeanor sentencings, judges ordered punishments that were lighter than what the government argued for in terms of jail or home detention. Two-thirds of defendants sentenced for misdemeanor pleas didn’t receive any jail time.

If you have more information about Jan. 6 or the legal fights in its aftermath, contact this reporter at zoe.tillman@buzzfeed.com, or see other ways to send tips here.

Prosecutors have not charged everyone accused of descending on the Capitol with felonies that reflect the political nature of the overarching criminal event, which temporarily halted Congress’ certification of the election and the peaceful transfer of power. No one has been charged with sedition or insurrection, both rarely brought offenses. A top Justice Department official said early on that sedition was being explored for “the most heinous acts,” along with conspiracy; more than 50 people have been charged with that latter crime.

Of the 700-plus people charged so far, BuzzFeed News’ analysis shows that just over half are facing at least one felony. The most common felony count is for obstructing an official proceeding; those cases have tended to involve some specific evidence that defendants were actively trying to disrupt the special session of Congress, such as making it to the floor of the Senate or expressing their intent in interviews or online. The obstruction offense has a maximum sentence of 20 years in prison, although nonviolent, first-time offenders are likely to face far less than that, and prosecutors have already agreed to let some defendants plead down to a misdemeanor. There are also felony cases pending against people charged with assaulting police, carrying or using weapons, and civil disorder.

Everyone else is being hit solely with misdemeanor charges for illegally being in the Capitol, disorderly conduct, and parading, a collection of counts carrying maximum penalties between six months to a year in jail. The US attorney’s office in Washington focused plea offers this year on the less serious cases with lower stakes. It’s a strategy that not only clears cases and frees up resources, but also is in keeping with broader trends across the US justice system, where the overwhelming majority of criminal cases end in plea bargains.

This process means that justice for an attack on democracy is filtering through a criminal justice system largely built around agreements that are hammered out in secret between the accused (the rioters) and the accusers (the prosecutors), and sentences crafted by a single judge. The riot was the violent culmination of a monthslong effort led by Trump and his supporters to undo millions of votes cast in a presidential election, but there’s little to no opportunity for public input on the consequences for people who participated.

Judges have talked from the bench about the challenge of applying the normal rules to an unprecedented event like Jan. 6. They’ve explained that they have to treat each defendant as an individual and can’t punish them for the full spectrum of criminal activity committed at the Capitol.

With most defendants admitting to the same misdemeanors on paper, judges are picking apart the details of their words and actions as compared to other rioters. They’re weighing how those details make a person more or less individually responsible for the threat — potential or actualized — posed by the mob.

How many minutes did a defendant spend in the Capitol? Did they walk through a breached door or climb through a broken window? Where did they go? How far inside did they travel? Did they capture photos or video? Did they take selfies, and did they look happy to be there? Did they witness violence or vandalism and keep going? Did they publicly brag about it online, or only send messages to friends and family, and does that distinction matter? Is the remorse they expressed later legitimate or are they just sorry they got caught, and, really, how can anyone know for sure?

And the big question that’s loomed over the conclusion of each of these cases: Is there any sentence that could dissuade people from storming the Capitol in January 2025 if they disagree with the results of the next presidential election?

For some judges, the obvious answer is jail. In the handful of cases where a defendant has pleaded guilty to a felony like assaulting police or obstructing Congress, judges have imposed months or years of prison. The length of incarceration in misdemeanor cases may be short by comparison, but judges have said they hope the threat of any loss of liberty scares off other people, disappointed or furious when the candidate they supported loses an election, from taking matters into their own hands.

US District Judge Tanya Chutkan has emerged as an early proponent of time behind bars for misdemeanor offenders. At a sentencing in early October, she ordered Matthew Mazzocco of Texas to spend 45 days in jail, becoming the first judge to go above the amount of time the government recommended. She chastised Mazzocco for treating the riot like “entertainment” — he’d posted a celebratory selfie in front of the Capitol on Facebook with the caption, “The capital is ours!” and took photos of himself smiling inside and outside the building — and said a harsher sentence was needed as a warning to others.

“There have to be consequences for participating in an attempted violent overthrow of the government, beyond sitting at home,” Chutkan said at the time.

Other judges aren’t convinced that time behind bars is justified for people pleading guilty to low-level, nonviolent crimes, or if a relatively short stint in jail is even the most effective way to make the punishment “hurt,” in the words of one judge. They’ve crafted sentences featuring combinations of probation, fines, home detention, computer monitoring, social media restrictions, mental health treatment, job training, and community service.

With new cases being filed every week, 71 sentences is too small a number to confirm patterns for how the rest of these cases will play out. There’s too little data, for instance, to say whether the political pathways that judges took to the bench manifest in the sentences they hand down. Judges nominated by presidents of both parties, including Trump, have mixed records of ordering jail versus probation for Capitol rioters. But most judges have only presided over a handful of sentencings, and some judges haven’t sentenced anyone yet.

Still, enough cases have reached the final phase to understand what judges are thinking about as they mete out justice. They’re aware of the intense media coverage of these cases and the fact that the court allows the public to dial in to hear live audio of most hearings, a pandemic-related expansion of access. They’re keeping an eye on the investigation into Jan. 6 that’s unfolding in Congress, and they’re paying close attention to what their colleagues are doing — sometimes publicly signaling when they agree or disagree with another judge’s decision or comments.

There was the case where US District Judge Trevor McFadden accused the Justice Department of not being “even-handed” in its response to Jan. 6 compared to the protests last summer against racism and police brutality — comments that prompted Chutkan in another case to say she disagreed with McFadden, calling it a “false equivalence.” It was one of the few times where the broader political discourse seemed to seep into public exchanges among judges; McFadden was nominated by Trump, Chutkan by former president Barack Obama. There was the case where US District Judge Rudolph Contreras accused prosecutors of ramping up their sentencing recommendations because they were yelled at by another judge.

Several judges have expressed concern about the case of Anna Morgan-Lloyd, who made an emotional plea for leniency to US District Judge Royce Lamberth and received probation. Morgan-Lloyd then went on Fox News the day after her sentencing and made comments that seemed to minimize the violence at the Capitol. Morgan-Lloyd’s lawyer has insisted her client got “played” by Fox and was honest with Lamberth, but judges have held up her case as a cautionary tale against giving too much weight to after-the-fact expressions of remorse.

Lamberth, meanwhile, has made it known that he felt burned by Morgan-Lloyd. When Frank Scavo of Pennsylvania came before the judge last month after pleading guilty to the same parading misdemeanor, Lamberth blew past the two-week jail sentence that the government argued for, sentencing Scavo to 60 days.

A few judges have complained that charging decisions by prosecutors tied their hands in crafting sentences.

US District Judge Amy Berman Jackson has questioned prosecutors about the wisdom of entering plea deals for a misdemeanor that restricted the options that judges had for ordering extended court supervision. US District Judge Carl Nichols expressed the same concern at a November sentencing for David Mish of Wisconsin, saying he was “very torn” because he thought Mish could benefit from longer-term contact with the court. Nichols ended up sending Mish to jail for 30 days, citing his previous criminal record as well as the need to deter others.

US Capitol Police via AP

Paul Hodgkins, 38, of Tampa, Florida, (holding flag) stands in the well on the floor of the US Senate on Jan. 6, 2021, in Washington, DC.

It’s not the first time that federal judges in Washington have been faced with novel questions of law with massive implications for the legitimacy of the US government and its institutions. The court has presided over legal entanglements from some of the biggest political scandals in modern history — Watergate, Whitewater and the Clinton affair, the Russia probe — as well as the crush of cases filed by people captured in the War on Terror after 9/11 challenging their indefinite detention at the US military installation in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

The sheer number of Jan. 6 cases sets this prosecution effort apart. A prosecutor recently said in court that the government believed that 2,000 to 2,500 people illegally went inside the Capitol, far more than the estimate of 800 people that a US Capitol Police official gave Congress early on. Prosecutors and Justice Department officials haven’t said if there’s a target number for when they’ll end the investigation.

The seven people sentenced for felonies have all received prison time. Paul Hodgkins of Florida, who pleaded guilty to obstructing Congress, had tried to argue for no time behind bars since he hadn’t engaged in violence or destruction; he went onto the Senate floor and carried a “TRUMP” flag. US District Judge Randolph Moss said probation wasn’t an option and ordered him to spend eight months in prison, less than the 18 months sought by prosecutors. It was a benchmark-setting hearing that spelled bad news for any defendant hoping to stay out of prison with a felony plea deal.

People needed to know that assaulting the Capitol and interfering with the democratic process “will have severe consequences,” the judge said at the time.

Of the 64 people sentenced for a misdemeanor offense, 36 — more than half — received sentences that were lighter than what the government recommended as far as loss of liberty, according to BuzzFeed News’ analysis. That included 14 cases where judges rejected the government’s recommendation of prison time altogether, nine cases where judges ordered a period of incarceration that was shorter than the government’s request, and 13 cases where judges didn’t agree with the government’s recommendation of a short period of home confinement as a condition of probation.

Forty defendants who pleaded guilty to misdemeanors — roughly two-thirds — avoided time behind bars, receiving home confinement and probation, or probation alone.

The remaining 24 misdemeanor offenders were incarcerated. Nine people received prison sentences that were more severe than what the government requested, with judges either going above the amount of incarceration prosecutors asked for or rejecting a recommendation of probation. Nine people received prison sentences that fell below the government’s recommendation, and six received time behind bars that matched the government’s request.

Jail sentences for misdemeanor offenders have ranged from as short as 14 days to as long as six months, although in the two cases to hit that high end the defendants already had been in jail after their arrests and were sentenced to the time they’d served.

US District Judge Thomas Hogan ordered Robert Reeder to spend three months in jail, less than the six months prosecutors argued for after new evidence emerged that he’d been involved in a physical confrontation with police. Hogan said he wanted his sentence to signal that other rioters should expect jail time. But he explained that he didn’t think six months was appropriate because Reeder didn’t have a previous criminal record and the judge wasn’t sold that the evidence showed Reeder deliberately struck an officer with his fist.

The person-specific facts of each case make it hard to do apples-to-apples comparisons, but some cases feature similar overarching narratives. Russell Peterson of Pennsylvania livestreamed on Facebook — “The Capitol is ours right now,” he said at one point — and prosecutors accused him of downplaying the violence afterward. The government asked for two weeks in jail. Jackson sentenced him to 30 days. Prosecutors wanted 60 days in jail for Glenn Croy of Colorado, arguing he’d entered the Capitol twice, treated the breach like a “vacation” by taking and posing for photos, and sent messages after that disputed the level of violence. Howell sentenced him to three months of home confinement and three years of probation.

Howell has used some of the strongest language this year denouncing the insurrection and questioning prosecutors’ decision not to press more serious charges against participants. But in several misdemeanor cases, she’s rejected the government’s jail recommendations, pointing to other cases where prosecutors asked for probation for rioters who pleaded guilty to the same crimes and saying she also had an obligation to avoid “unwarranted” differences. She blasted the government’s “muddled” approach and blamed prosecutors for undercutting their own efforts.

Howell’s sentences have included a period of home confinement and probation for Jack Griffith, a Tennessee man who was recorded on video screaming in excitement as he entered the Capitol and whose extensive social media posts afterward suggested a lack of remorse. Prosecutors had asked for three months of incarceration. As part of his sentence, Howell ordered the probation office to monitor his computer activity and barred him from using any social media platforms without getting permission first.

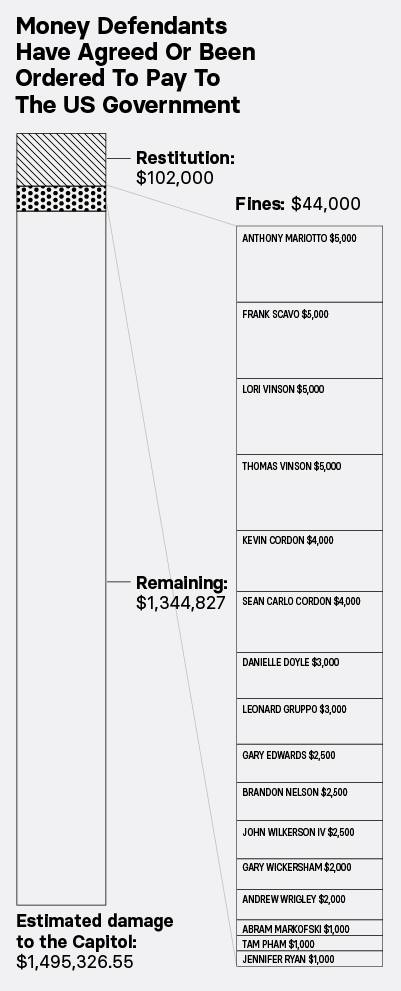

Some judges have turned to hitting people’s pockets. In 16 cases, judges ordered defendants to pay fines ranging from $1,000 to $5,000 as an additional penalty beyond probation or jail; in 13 of those cases, the sentences were otherwise lighter than the government’s recommendation.

Fines levied by judges are on top of agreements defendants have made to pay restitution to the US government as part of their plea deals — $500 for a misdemeanor plea, and $1,000 to $2,000 for a felony plea. Between fines ordered by judges and restitution agreements, the 160-plus rioters who have entered guilty pleas owe $148,500, roughly 10% of the nearly $1.5 million that the government has estimated in damage to the Capitol.

When US District Judge Reggie Walton sentenced the Vinsons, overruling the government’s request for jail time for Lori Vinson, he explained that one reason for that was he didn’t think the cost of incarcerating her was worth it. He said that he’d rather have the couple contribute toward the cost of repairing the Capitol and jail would only delay their ability to do that.

“I want the sentence to hurt, because people have to understand that if you do something like this, it’s going to hurt,” Walton said, ordering them each to pay $5,000.

Walton took the same approach this month in sentencing Anthony Mariotto of Florida. The prosecutor asked for four months of incarceration, arguing his misdemeanor case was more serious because of how far he’d made it into the building — he posted a selfie on Facebook from the Senate gallery, smiling, with a caption that included, “This is our house” — and the fact that he recorded assaults on police, knocked on doors, and seemed to minimize his role in an interview later.

Walton sentenced Mariotto to pay a $5,000 fine and spend three years on probation. The judge said he believed that participating in the insurrection was a serious enough offense to merit incarceration. But he said he also didn’t think it was realistic to try to jail every defendant, and that it wouldn’t be appropriate since other defendants who pleaded guilty to the same crime received probation.

Some judges have used the public platform they have at these sentencing hearings to make their feelings about what happened on Jan. 6 known. They’ve emphasized the seriousness of the insurrection, disputed narratives that have sprung up among right-wing politicians and pundits that rioters were “tourists” or that incarcerated defendants are “political prisoners,” and called out some of the bold-face names who haven’t been criminally charged — Trump and his allies who promoted the lie that the 2020 election was stolen (and continue to do so).

When US District Judge Rudolph Contreras earlier this month rejected the government’s request for jail time for Felipe Marquez of Florida, the judge explained that he believed Marquez would be better served by home confinement and probation, plus a set of additional conditions including mental health treatment, job training, and other support. The judge said that Jan. 6 was the result of an “unprecedented” series of events, spurred on by Trump and his allies who “bear much responsibility” for what happened.

At a sentencing in November, US District Judge Amit Mehta said that defendant John Lolos of Washington state was “a pawn in a game that’s played and directed by people who should know better.” Prosecutors wanted 30 days in jail for Lolos, who entered the Capitol through a broken window, chanted in support of the mob as he walked through the building, and yelled, “They left! We did it!” as he left. He came to law enforcement’s attention when he was kicked off a plane after the riot for being disruptive and chanting, “Trump 2020!” Mehta sentenced him to 14 days.

“People like Mr. Lolos were told lies and falsehoods and told that an election was stolen when it clearly was not,” Mehta said. “Regrettably, people like Mr. Lolos for whatever reason are impressionable and will believe such falsehoods and such lies … and they are the ones who are suffering the consequences.”

No judge has found that individual rioters weren’t culpable because they were corrupted by online conspiracy theories or inspired by Trump.

“No one was swept away to the Capitol,” Jackson said at Russell Peterson’s sentencing this month. “No one was carried. The rioters were adults. And this defendant, like hundreds of others, walked there on his own two feet and he bears responsibility for his own actions. There may be others who bear greater responsibility and who also must be held accountable, but this is not their day in court, it is yours.” ●